In 1931, an unknown English actor named William Henry Pratt walked into Universal Studios’ makeup chair as a struggling journeyman. Four hours later, he emerged as Frankenstein’s Monster—and Boris Karloff was born. What followed wasn’t just a career. It was the creation of cinema’s most enduring monsters and the establishment of horror’s fundamental language.

But here’s what makes Karloff’s story truly extraordinary: beneath every terrifying creature he portrayed lived the soul of a gentle cricket-loving gentleman who grew prize-winning flowers. The man who gave nightmares to millions was, in real life, so soft-spoken that children adored him.

This is the story of how one man’s characters literally invented modern movie monsters—and why his creative legacy still haunts cinema today.

The Monster That Changed Everything

Frankenstein (1931): Birth of an Icon

When James Whale spotted Karloff in Universal’s cafeteria, he saw something others had missed. Those sunken cheeks, that angular face, the naturally gaunt appearance—it was as if nature had designed the perfect canvas for movie monster makeup.

But Bela Lugosi had already turned down the Monster role. Why? Because there was no dialogue. No recognition. Just grunts and groans beneath heavy makeup.

Karloff, desperate for work after 20 years of struggle, said yes immediately.

What happened next changed cinema history.

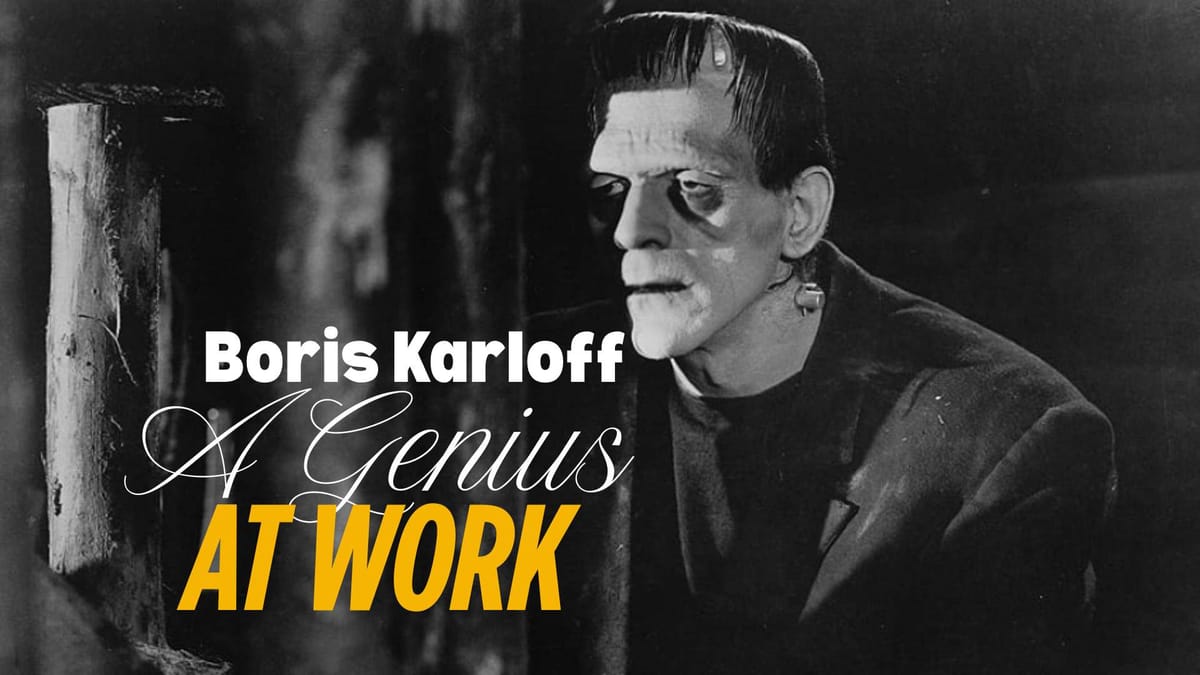

Jack Pierce, Universal’s master makeup artist, had been developing something revolutionary. Working with Karloff for six months, they created not just makeup, but an entirely new visual language for movie monsters.

“The Monster wasn’t just a creature—he was cinema’s first sympathetic anti-hero.”

The process was brutal. Every morning at 3:30 AM, Karloff endured four hours of agony as Pierce built the Monster layer by layer:

- Cotton and collodion formed the facial structure

- Mortician’s wax created those iconic droopy eyelids

- Green greasepaint (to appear pale on black-and-white film) covered his face

- Metal electrodes glued to his neck left permanent scars

- 48-pound costume with steel rods down his legs created that lumbering walk

The transformation was so complete that Karloff lost 25 pounds during filming. But he never complained. Even when the makeup removal process each evening left him scarred for life.

The result? Pure magic. Karloff’s Monster wasn’t just scary—he was heartbreaking. When the creature accidentally drowns the little girl, believing she’ll float like a flower, audiences wept for the Monster, not his victim.

Mary Shelley had dreamed of a creature that would make readers question who the real monster was. Karloff and Pierce achieved exactly that.

Creating Cinema’s Second Greatest Monster

The Mummy (1932): Imhotep’s Eternal Love

Fresh from Frankenstein’s success, Universal wanted lightning to strike twice. They handed Karloff another monster role, but this time the transformation would be even more extreme.

The Mummy required eight hours of daily makeup application. Pierce wrapped Karloff in authentic-looking bandages, layer by layer, then aged them with special techniques to appear 3,700 years old.

But Karloff appears as the traditional wrapped mummy for only minutes. The real genius was Imhotep, the ancient priest disguised as modern Egyptian Ardeth Bey.

Pierce aged Karloff’s face to look millennia old—every wrinkle, every line suggesting centuries of existence. The effect was so convincing that audiences believed they were seeing an actual ancient being.

The character’s motivation made him unforgettable: Imhotep wasn’t evil for evil’s sake. He was driven by love—attempting to resurrect his beloved Princess Ankh-es-en-Amon through her modern reincarnation.

“This wasn’t about scaring audiences. It was about showing them that monsters could love, could suffer, could be more human than humans themselves.”

Karloff’s performance combined menace with melancholy. When Imhotep finally crumbles to dust, audiences mourned his destruction despite his murderous methods.

The Monsters That Followed

Beyond the Universal Trinity

While Frankenstein’s Monster and The Mummy remain Karloff’s most famous creations, his character work extended far beyond these icons:

The Black Cat (1934) – As Hjalmar Poelzig

Karloff created perhaps cinema’s first war criminal, a Satan-worshipping architect who commanded death camps. The role was so ahead of its time that it wouldn’t be fully understood until after World War II.

Bride of Frankenstein (1935) – Returning as the Monster, Karloff added new layers of pathos. His delivery of “Friend!” and “Bride!” showed an evolving creature learning language and emotion.

The Body Snatcher (1945)

Working with producer Val Lewton, Karloff crafted John Gray, a cabman who robs graves by night and pets cats by day. The moral complexity was staggering.

Targets (1968)

In his final major role, Karloff played Byron Orlok, an aging horror star confronting modern violence. It was essentially Karloff examining his own legacy.

The Gentleman Behind the Monsters

The Real William Henry Pratt

The irony of Karloff’s career never escaped him. This gentle soul who spoke in refined English tones became synonymous with cinematic terror.

Born into privilege as the youngest of nine children, Karloff was educated at King’s College London. His family expected him to join the diplomatic corps like his brother Sir John Thomas Pratt.

Instead, he dropped out, emigrated to Canada, and spent two decades struggling as “Boris Karloff”—a name he chose because it “sounded foreign and exotic.”

The physical toll was enormous. Years of manual labour while pursuing acting left him with permanent back problems. The heavy monster costumes and makeup processes damaged his health further. By his later years, he required oxygen tanks between takes.

Yet he never complained. Fellow actors universally described him as kind, professional, and utterly lacking in ego.

Christopher Lee, who lived next door to Karloff for years, often spoke of his neighbour’s gentle nature:

“He was the most considerate man I ever knew. Children would literally run up to hug him on the street, even recognising him as the Monster. He had that effect on people.”

The Master’s Technique

How Karloff Made Monsters Human

What separated Karloff from other horror actors wasn’t just the makeup or the physical presence. It was his approach to character.

He studied each monster like a classical role:

- Researched medical texts to understand how a reanimated corpse would move

- Worked with Pierce to ensure makeup supported character motivation

- Created backstories for even minor monster roles

- Used his classical training to find the humanity in every creature

The eyes were everything. Even beneath the heaviest makeup, Karloff’s expressive eyes conveyed complex emotions. The Monster’s confusion, Imhotep’s ancient sadness, the pathos of creatures caught between life and death.

His philosophy was simple: “The object of the roles I played is not to turn your stomach—but merely to make your hair stand on end.”

Cultural Impact and Modern Legacy

The Template for Every Monster Since

Walk through any modern horror film and you’ll see Karloff’s influence:

The sympathetic monster – From King Kong to Edward Scissorhands, every complex creature owes a debt to Karloff’s nuanced performances.

Physical monster design – The bolt-necked, flat-topped Frankenstein look remains the definitive image 90+ years later.

Makeup artistry – Every prosthetic effect builds on Pierce and Karloff’s innovations.

Performance style – The way actors move and breathe life into monster roles traces directly back to Karloff’s techniques.

Rick Baker, seven-time Academy Award-winning makeup artist, calls Karloff his primary inspiration:

“Without Boris Karloff, there would be no modern monster movie. He didn’t just play creatures—he gave them souls.”

The Philosophy of a Monster King

Karloff’s Insights on Fame and Art

Despite achieving instant fame with Frankenstein, Karloff remained remarkably grounded. His quotes reveal a thoughtful artist who understood his place in cinema history:

“Certainly, I was typed. But what is typing? It is a trademark, a means by which the public recognises you. Actors work all their lives to achieve that. I got mine with just one picture. It was a blessing.”

He embraced his monster image while maintaining perspective:

“When I was nine, I played the demon king in ‘Cinderella’ and it launched me on a long and happy life of being a monster.”

Even success couldn’t change his essential nature. When asked about his appeal to children, Karloff observed:

“I don’t really scare them any more than do Jungle Jim, Dan Dunn, Tarzan, and the other heroes of the comic sections.”

The Final Performance

Targets (1968): A Meta-Masterpiece

Karloff’s last great role was his most personal. In Peter Bogdanovich’s debut film, he played Byron Orlok, an aging horror star questioning his relevance in a world of real-world violence.

The parallels were unmistakable. Orlok, like Karloff, represented old-school monsters facing modern meaningless killers. The film asked whether traditional scary movies mattered when daily news delivered actual horror.

Karloff was only hired for two days. But he was so impressed with Bogdanovich’s script—written specifically for him—that he worked additional days for free.

The film became his artistic goodbye. Karloff died just months after its release, but not before creating one final masterful character study.

Why These Characters Matter Now: The Enduring Power of Karloff’s Creations

In our current era of CGI monsters and jump-scare horror, Boris Karloff’s character-driven approach feels revolutionary again. His creatures worked because they made audiences think and feel, not just scream.

Modern filmmakers still study his work:

- Guillermo del Toro cites Karloff’s empathetic monsters as inspiration for films like The Shape of Water

- Doug Jones uses Karloff’s movement techniques for contemporary creature roles

- Horror directors from James Wan to Ari Aster reference Karloff’s performance philosophy

The lesson remains powerful: great monsters aren’t about effects—they’re about humanity.

Boris Karloff created more than famous characters. He established the emotional architecture of modern horror cinema. Before Karloff, movie monsters were simple bogeymen. After him, they became complex beings worthy of our sympathy, fear, and fascination.

His characters live on in every sympathetic villain, every misunderstood creature, every monster movie that asks us to question who the real monster is.

I find it remarkable how the cricket-loving English gentleman who became Hollywood’s Monster King proved something profound: the best art comes from finding humanity in the inhuman, beauty in the grotesque, and truth in the fantastic.

William Henry Pratt may have died in 1969, but Boris Karloff’s monsters remain eternal—still teaching us about compassion, otherness, and what it truly means to be human.

“In the end, the real magic wasn’t in Jack Pierce’s makeup or Universal’s laboratories. It was in Boris Karloff’s ability to make us love the unlovable, fear the familiar, and see ourselves in cinema’s greatest monsters.”