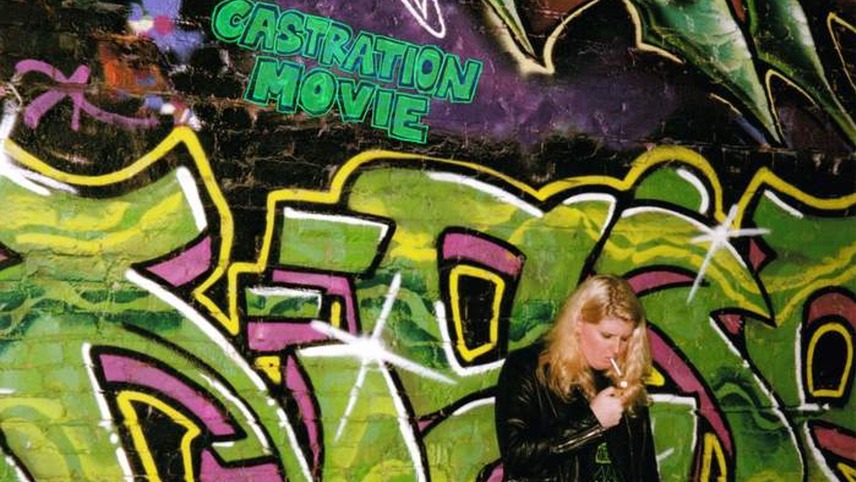

Castration Movie

Castration Movie Louise Weard is obsessed with castration. The idea for her five-part DIY epic Castration Movie came when she was reviewing footage for a supercut of onscreen “dick destruction” subtitled Texas Birth Control—and, she notes with amusement, eating little phallic pickles.

Weard has an infectious laugh, and the things she finds funny tend to reflect her unique form of good-natured miserablism. Her characters are marginalized people who get the shit beaten out of them, physically and emotionally. Some are marginalized in ways that attract sympathy from her audience. Others, like the incel who’s the protagonist of the film’s first chapter, are not. Either way, their suffering is fodder for abject cringe comedy, and Weard puts herself at the center of the narrative as a “nightmare side” of herself named Michaela, a.k.a. Traps, a trans sex worker whose combative personality is armor over a profoundly lonely heart.

Empathy is at the heart of Weard’s project, and not in the cloying, insincere way the word is sometimes used. In Castration Movie, Weard erects barriers to audience engagement—grainy Hi8 footage, an extended 275-minute run time, explicit sex and nudity, long mumblecore dialogue scenes—almost as a test. (Weard estimates that Castration Movie will clock in at about 12 hours in its complete form.) Can you see through all of that and engage with the earnest humanity within? Those who can are rewarded not only with a lightning-in-a-bottle portrait of trans life in the early 2020s, but, as Weard puts it, a larger statement on how “the internet has made us tribal and crazy, and that’s not good.”

The first two chapters of Castration Movie, subtitled Castration Movie Anthology I: Traps, were completed in 2024. Weard began shooting the next segment, The Best of Both Worlds, in April 2025; we spoke in May, and she was very enthusiastic about the footage she had already captured by that point. I saw a scene from The Best of Both Worlds where Michaela gives what she thinks is good, practical advice to a group of early-transition transfemmes—she ends up offending all of them, of course—as well as a scene where she’s gently corrected for her misstep by two volunteer leaders played by filmmakers Jane Schoenbrun (I Saw the TV Glow) and Sepi Mashiahof.

Following a successful series of one-off screenings from Glasgow to Seattle, Castration Movie Anthology I: Traps was acquired by Muscle Distribution, a new label from NYC-based programmer and archivist Elizabeth Purchell, in May of 2025. It made its U.S. festival premiere at the long-running Frameline festival in San Francisco on June 23.

Louise and I met at the premiere of 100 Best Kills: Texas Birth Control, Dick Destruction at Fantastic Fest in 2022 and have remained friends since then. The conversation just started rolling when we got together for a more formal interview, so the transcript begins in medias res as well.

Louise Weard: That’s the dream of filmmaking, playing Barbies with real people and their lives. I do wonder if the analogy comes from me being a trans woman. I didn’t have a traditional childhood playing with dolls, so as an adult I’m sublimating that into this horrible filmmaking thing where the people are the dolls.

Filmmaker: You’re shaving the Barbies’ heads and rubbing them in the mud. Metaphorically.

Weard: I also wanted to have a childish style as a sort of anti-aesthetic. Too many movies are reliant on homage and pastiche for their cinematic language. I hate that. I wanted to go in the opposite direction, as if I’d never seen a movie before I try to give the camera to people who don’t have experience, because to me, it’s all about that zoom functionality. The zoom is where the magic is, and people who are too experienced don’t think to use the zoom.

Filmmaker: Why did you want the film to have this childlike sensibility?

Weard: There’s this weird perpetual adolescence our culture is stuck in where we’re trapped in this liminal space between adulthood and childhood. That’s what my movie’s tapping into, as well as the way that feeling is sublimated through the internet and how that causes bad behavior. But it’s not a coming-of-age movie, more an exploration of the hysterical reality we live in.

Filmmaker: Adolescents have famously poor impulse control. Is that how your characters behave?

Weard: That’s how the internet’s made everybody. One of the reasons I loved to play with 4chan when I was younger is that it was an anonymous place. There was something kind of sacred about playing into this childish desire to say the stupidest crap you could think of. Now it’s less fun, because you can see your uncle, under his real name, say the most heinous thing you’ve ever seen in your life on Facebook. We’ve crashed down the barrier that used to exist between online and real life. Some people approach the real world as if it were the internet, and that’s definitely what the characters in my movie do.

Filmmaker: Is Michaela a way of anonymizing your experience? Is she your screen name?

Weard: When I was approaching the cast, particularly those who were playing bigger characters, I would literally say to them, “The whole idea of the movie is that we’re going to merge the impression of this character with the worst qualities I see in you as a human being. We’re going to play into the nightmare side of yourself.”

Filmmaker: I love the idea of you going up to someone and saying, “Here’s everything that’s bad about you.”

Weard: There’s definitely a degree of finessing involved. I would grab my friends and say, “You can be shy or self-critical in this way. Let’s elevate that to be the one thing about your personality.”

Filmmaker: How does it work with people you don’t know as well?

Weard: It helps that I, as the director and star, put myself through the worst of it. I’m one degree removed from anyone who makes sense to be in Castration Movie in the first place. It started with my core friend group, and when we needed to add people a lot of them were people I had been working with [on sets in Vancouver]. People actually love doing it. It’s like therapy. Having the freedom to play into your worst traits is a very freeing process. For me, what’s fun about going into Michaela is I get to say heinous shit without consequences. I’m really not that much of a sociopath or a narcissist, but it was fun to play into that. People will say to Michaela, “Do you have no empathy?,” which is the funniest thing for this character who’s trying so hard to be empathetic and to learn. That’s kind of the mission statement of the movie—people who commit these really brutal social faux pas, but in their heads, they’re doing the right thing. There’s not a lot of direct internet stuff [in the movie], but it always feels like it’s in conversation with the way we interact online.

Filmmaker: Even talking about empathy—that’s such a buzzword online. It’s used so often, and so broadly, that it starts to lose meaning.

Weard: That was one of the ways that I wanted this movie to function. I’m taking all these groups that are considered degenerate in some way, not just in terms of sexuality, but politically as well: the incel, the TERF, the trans woman, the detransitioner, the adult baby, the cheating husband. I’m taking all of these archetypes and putting them all together in one movie where the basic throughline is to show you these people at their worst and still try to make you empathize with them in some way.

Filmmaker: Do you anticipate getting pushback from people who are offended by you relating certain ideologies with transness?

Weard: There are also very normal trans characters who just get to exist, but I’m focusing on a terminally online trans woman who really does see her identity as this house of cards. That’s why I wanted to write [Michaela] in the first place—I wanted to write a trans woman who had really bad politics. If you look at the UK press in particular, they’ll find a “one of the good ones” trans woman who’ll be like, “I identify as a trans woman, but at the end of the day, I’m a biological male.” I wanted to tap into that reactionary mindset.

What also inspired Michaela was seeing a tweet where someone said, “‘We can’t just let it slide when a trans [person] had a Nazi phase before coming out.” I started thinking about how funny it is for a Nazi to transition and be like, “Oh, now I’m just a normal girl,” like the political slate is wiped clean. All of the [characters] are finding community in extremely toxic places online, but just because those places are toxic in their ideology, it doesn’t make the connections they’re forming there any less real.

Filmmaker: There was a quote in the interview you did with The Guardian where you said that the movie trains you how to watch the next chapter. Can you elaborate on that?

Weard: Each chapter is teaching you the language to engage with the following chapter. It’s sort of a “frog and boiling water” approach, where by the time you get to the scene where you have me in a room with a bunch of right-wing provocateurs saying heinous shit, you can understand everything that led to that point. Each character is giving you the lens by which to view the next character. For example, an incel is the primary protagonist of the first chapter [of Castration Movie]. He’s a cis man who’s having this gender failure where he’s failing to live up to expectations of what it means to be a “real man.” So, he’s fighting and working out all of these masculine activities. You learn from the arc of his story how to view a movie about someone who gets hyper-focused on expressing their gender, and how that bounces off the people around them. Then we go into Michaela’s story. I think a lot of audience members, whatever their background, are used to being able to engage with a straight white male character.

Filmmaker: Yeah. It’s the default human in American cinema.

Weard: So, that’s an easy way to access the movie. You’ve had a full feature film with this guy. Now we go to the upper-level course, which is that we’re going to look at a trans woman. You’ve done the intro study on how to engage with gender through this character that is the default for cinema. Now we’re moving into a trans woman character—we were creating a new language of how to explore the trans woman on camera through this [movie]. But you’re not fully alienated as an audience member, because it’s using the same modes of how the previous character was shot and lensed and the way the patterns of the scenes are constructed. The upper-level course is like a full 90 minutes longer than the first one. [Laughs] You’re in that world a lot longer. But everything you’re seeing with Michaela was something that you were prepared for, whether you noticed it or not, with the Turner character.

The [third chapter] goes into a cis woman character who’s a TERF. She has a much more extreme exclusionary identity—she doesn’t believe that her partner is a trans woman, and becomes quite bigoted in how she discusses that idea. But you’ve just spent a long time with a trans woman, so you’re going to bring empathy into this next story. It’s like, “I’ve just been with these trans people for three hours. I understand the community they have.” If I’m trying to lend empathy to the TERF character, that’s not going to overshadow what we’ve already learned from watching Michaela’s story.

Filmmaker: It’s an interesting choice, because you’ve already established a rapport with these trans characters, then you challenge people by asking them to empathize with someone who hates them.

Weard: What I think is so interesting about it is that then you’re going from the TERF lens back into the character of Michaela, and her world with the movie having jumped forward a year and a half. She’s in a trans relationship that is based around some kink dynamics that you’re now interpreting through the perspective of the TERF character.

Filmmaker: That’s interesting.

Weard: But with Michaela, I’m playing it in this way that’s very empathetic again, so now you’re being pushed to put these things in conversation. At the end of the day, I want this movie to explore common humanity and say that, even though we might have differing opinions on things, we’re still people at the end of the day and extend some degree of understanding. I tried to write characters that had a very deep pain that is driving them into these places. If I was to put myself in their shoes, could I make them the hero of their own story?

The TERF was one of the most interesting to write, because I wanted to make sure that you can understand why she moves into that ideology. That’s so obviously so distant from my life experience.

Filmmaker: Well, I’m curious, because when you came out as trans, you were married to a woman, but she was supportive. So, this is like a nightmare version of what could have happened.

Weard: I literally recreated the experience of when I came out to my former partner, Dionne Copland. We’re still very close friends. We talk all the time, like every day. We still make movies together. She plays Michaela’s ex-wife in Castration Movie. We’ve had a lot of fun playing it up as a joke, because when I came out, I was doing the dishes, then I just had this moment where I was like, “I’m going to finally do this.” So, me and Dionne had a chat and she was so supportive. She was like, “It’s about time.” Then I write this scene where there’s this character doing the dishes. But [in the movie], their coming out is handled in a way where they’re really immature about it and their partner is very immature about it. It’s escalating in this way where they both suck, but I wanted the audience to be on her side. I wanted to create those dynamics in a way where you don’t agree with what [she’s] saying—you shouldn’t—but you can understand where she’s coming from.

It’s so tough politically right now, when trans people are having their rights taken away, to continue working on this project. But all this stuff has been planned out since 2022. Now in 2025, I’m shooting a chapter of this film where it’s making a character who’s anti-trans sympathetic. But I think good can come out of showing differing perspectives as well as commonalities. My hope would be that, because I have this sympathetic TERF character, that someone who shares those views would check out the movie and maybe find this common empathy.

Filmmaker: And watch it all the way through. Don’t just watch that chapter.

Weard: That’s the thing. I would hope that they would watch the whole thing, and understand that we’ve all gotten too crazy because of the computer. That’s the thesis I want people to take away from this. We really don’t film screens that much, but [the whole movie] has an online sensibility. We know these people are online through the way they talk, the way that they’ve built their ideologies. The only times I’m filming a computer screen, the camera is zoomed in and shaking super crazy so you can’t really see what you’re looking at.

Filmmaker: I can’t imagine the camera you use picks up screens all that well. It’s what, a mini DV?

Weard: I got it right next to me. It’s a Sony Digital8 Handycam. The DCR-TRV330.

Filmmaker: How long have you had that thing?

Weard: The one I’ve got right here on my desk is the newer one. I also have a second camera, which is my childhood one. We shot most of Castration Movie Part 1 on that—the scene with Vera [Drew] was the last thing we shot in part one on my original childhood camcorder. It started having an internal error, and when I Googled how to fix it, what you had to do was slam the camera against a wall and hope it started working again.

Filmmaker: Are you serious?

Weard: It’s really funny because both cameras do that. It can’t register the tape or whatever. When I was in Montreal, I handed the camera to my friends, like, “Hey, can you film my Q&A?” And when I walk back after, they go, “Louise, we had this weird error show up on the camera, and I know it’s gonna sound crazy, but it says online that the only thing to fix is to slam it against the wall.” So yeah, they’re not the best.

Filmmaker: Do you ever have multiple cameras going at the same time?

Weard: No, it’s only ever one camera. If we have a second camera going, it’s just for behind the scenes.

Filmmaker: The parallels between the incel storyline and the Michaela storyline are really beautifully constructed in the way they build to similar crisis points. Did you find that in the footage?

Weard: No, that was part of the structure [from the beginning]. The whole movie’s in my head. The plan is to do that five times with that same structure, with five different characters all going through some crisis, and every one of them ends with a different interpretation of the “bursting into a room to have the big breakup” scene. My main process is what I call collaborative screenwriting. I hate writing. I find it to be too lonely, and my whole reason for making films is to work with other people and be collaborative. The whole movie’s in my head. I keep it structured to interpret it for other people. I’m bad at it, because a lot of times I’m grabbing people and I don’t really tell them what we’re doing until we’re on set doing it.

This might be the first movie ever written in Microsoft Excel. Here, I’ll show you.

Filmmaker: Wow, it is in Excel. It’s a series of script beats organized in Excel. And is this chronological?

Weard: It’s chronological, top to bottom. We have three chapter threes, because I’m a psychopath. But yeah, it’s scripted in Excel.

Filmmaker: You don’t storyboard or anything like that?

Weard: No, it’s just what’s in my head. The Excel spreadsheet’s less comprehensive than what’s in my head at any given time.

Filmmaker: I would not trust myself that much.

Weard: This movie’s example of channeling the divine in some ways. I don’t need to write it down, because it’s going straight from this divine source into the film. I’m just the conduit to make this work of art. I only made trash before this, and then after this movie’s done, I’m just going to continue making trash. I did a good job once, and then never made anything else of note. I like the idea of that.

Filmmaker: When you say you don’t tell people anything before you film, how extreme is that?

Weard: We have costumes. I have a production designer. But directing is all about communication, and with my closer crew—my camera operator, my assistant directors—there were times where I would be very spur of the moment. I would have to catch them up while I was turning the camera on, and I can be very excitable, depending on what we’re doing. Here’s an example: Jane Schoenbrun and Sepi Mashiahof [were in Vancouver], and we were out for drinks on a Wednesday. I said to them, “Oh my God, you gotta be in the next chapter of Castration Movie.” So, Friday, the morning of the shoot, I woke up and messaged Jane and Sepi, like, “Hey, I’m feeling tonight. I want to come out.” And they were like, “Hell yeah, we’ll be there.” We shot for three hours and about 45 minutes is going to go in the [upcoming second part of the] movie.

Filmmaker: You knew what characters you wanted them to play when you showed up?

Weard: Yeah, we had all that planned. I prepped Jade and Sepi on the parts, which had been written forever. Actually, when I wrote it, a part of me thought it’d be funny to get Jane in that role—trans directors having this conversation about respectability.

Filmmaker: There is a meta aspect to it.

Weard: All filmmakers think like this, but my movie is also a movie about movies. So much of the film is commentaries on ideas. One of my favorite scenes in Castration Movie part one is the scene where I get pissed on. Obviously, the central image of that scene is like, “Oh my God, here’s a director getting pissed on on camera.” But what’s important is what’s happening in the foreground, where these two girls are having an argument about the aesthetics of how to shoot sex work and how the form is dictated by the medium by which the viewers will see it. It’s a meta-commentary on how to shoot sex work in this movie that is making all these choices to reframe and rethink how we shoot sex work and trans bodies, all these things that have not traditionally been in the forefront of cinema.

Filmmaker: What do you mean by rethinking how we film trans bodies?

Weard: One of the really big points I wanted to make is that there’s no touristic gaze in my movie. I’m not going to hold people’s hand and say, “It’s okay. Look how pretty she is!” On the one end you have these leering, sexualized looks at trans bodies. On the other is the pitiable trans body, like Eddie Redmayne in The Danish Girl —this sad creature who’s gonna get surgery and die. They’re entering trans identity from this outsider perspective where the idea is to try to make a cinema of attraction. “Hey everyone, come look at the freak,” you know?

I don’t want to have that gaze. I don’t want to recreate it. We’re building a trans gaze from the ground up. For my movie to be oppositional to the tourist gaze, it’s got to have ideas like normalizing my body on screen. It’s a locked off shot from across a room where you’re just watching me have a very typical morning routine. It’s the Chantal Akerman approach, the idea of showing you the mundane in order to normalize [a character]. Now your lens by which you view them is much more intimate than you’re accustomed to. I’m alongside a bunch of other filmmakers who are starting to get more mainstream approval of our work. I don’t want to say that there wasn’t a lineage of trans filmmakers before us who created the foundation, but because of the internet, there’s a degree of accessibility around [trans filmmakers] that allows us to be in conversation with each other.

Filmmaker: How committed are you to the idea of an anti-aesthetic? Do you ever find yourself thinking, “Oh, that’s a nice shot?”

Weard: I block everything with the camera because the [cast and crew] need to know what we’re doing, but I like to leave room for spontaneity. Where my excitement is as a director is in the stuff I can’t predict, because I think that the best parts of movies come from the spontaneous and improvisational. I always go back to the audio commentary for The Warriors where you have Walter Hill saying, “This got fucked up. This didn’t go right.” And it was every good moment of that movie. I remember internalizing this idea of, “When you have to solve a problem, that adds character to a film that makes it unique and special and good.” So in a way, I’m forcing a process that allows for that to continuously happen.

Filmmaker: Does the spontaneity ever feel forced?

Weard: I’ve developed a process where it doesn’t have to feel that way. When I sit down with the actors, depending on who it is, there’s going to be more or less [instruction]. If I’m working with non-actors, it’s more by the book: “You say this, then you walk over here, you bite this donut, and you sit down over here.” But sometimes I’m working with actors whose comedic timing I trust, so I don’t need to tell them everything. Like with Vera and Cricket [Arrison] — we actually had something totally different for them to fight about [for their scene in part one], but five minutes before we started shooting Vera said, “Can we try one where we fight about Dune?” That was very close to something that was actually happening [at the time]. And it’s one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen.

What I usually do with everyone is give them a character history, so they know what brought them into that moment, then they can react based on that. It’s pretty normal directing, it’s just instead of having words on a page that I want people to nail, I’m giving people the impression of a script. I tell everyone, “We’re only doing one take of this. So just try to get the impression of what we said. Find the timing yourself.”

Filmmaker: So pretty much every scene in the movie is one take.

Weard: The only time we do an extra take is if something goes completely wrong. I’m editing on the day, so we have to make sure that we know how we’re coming into a scene, how we’re coming out of it, and that everything happens in [a way] that is perfectly structured. It’s also about finding the funny, because to make a movie this dark it has to be funny. The way that you can get away with having these scenes that go on a long time is finding a punchline to go out on. While I’m shooting, I’m thinking about it as a director, performer and audience member, so I can really play into the edit, too.

Filmmaker: As the editor, you’re the first audience member.

Weard: I’m amazed that people like this movie, because when I went into it, I wanted to make my own favorite movie. And the fact that a bunch of other people like it fits into this feeling I’ve had for a long time, which is that the death of cinema is happening because everything is trying to be so universal in its scope. Marvel films are trying to play to every demographic, so they lose the specificity that allows for empathy to enter into the picture. I think it’s through specificity that things actually become universal, because we find a common humanity with something that’s depicted really authentically. That allows us to enter into that story, and feel less alone, and that’s what movies are for. You can be specific. I don’t think it’s alienating. We go through life every day and aren’t privy to the internal world of every person we interact with. But we can still communicate. As a filmmaker, I make movies to connect with people so that as a group, we all feel less alone by being in conversation with each other through the work. I’m a profoundly lonely person. That’s why I create art.

Even though it’s written as a tragedy, I think this movie functions best as an extremely dark cringe comedy. It’s in conversation with the work of Matt Johnson or Nathan Fielder, where you’re playing in this zone of, “When is this real and when is it fake?” When I get asked at Q&As if something was real, I say, “Yes, it is. Or maybe not.” I’m never going to be specific on what is or isn’t real in the movie.

Filmmaker: Do you think that all the sex and nudity in Castration Movie piques people’s interest in a voyeuristic way?

Weard: I thought that if I did a bunch of sex and nudity for real, the audience would never question the world of the film. There’s stuff in part one that isn’t real sex, and there’s stuff that is for sure real sex. It would surprise people what is real and what isn’t. The movie’s going to end with this DIY surgery, right? And whether I do that for real or fake it, I want the audience to have lost trust in me in the same way Tobe Hooper does in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, where they don’t trust me not to show them something they can’t come back from. I think it’s fun to play in that zone of high art and low art, between Last Tango in Paris and August Underground.

Filmmaker: Do you think it matters if it’s all real or not?

Weard: That’s what’s so fun—by the time I’m getting pissed on in part one, the audience is laughing along with it. I only realized how crazy that is watching it in a movie theater. People warm up to it in a way where they’re not even thinking about it as a transgressive film image. When I made the film, I put a lot of love in it. When I promote it, I play into the “This is the craziest film you’re ever going to see!” stuff, but there’s too much love in it for it to really be an edgelord film. The whole point of it is to show you human behavior and try to make it feel as normal as possible. If I’m changing an adult baby’s diaper, I want it to be a tender, beautiful moment, the way that person would see it in real life. I never want to point and laugh at somebody who’s earnestly expressing themselves. It’s all about the way they’re communicating with the world around them and staying in the perspective of a character who is committing these social faux pas. It’s a movie about how it’s okay to be cringe. It’s about letting go of whatever’s repressing your most cringe self.