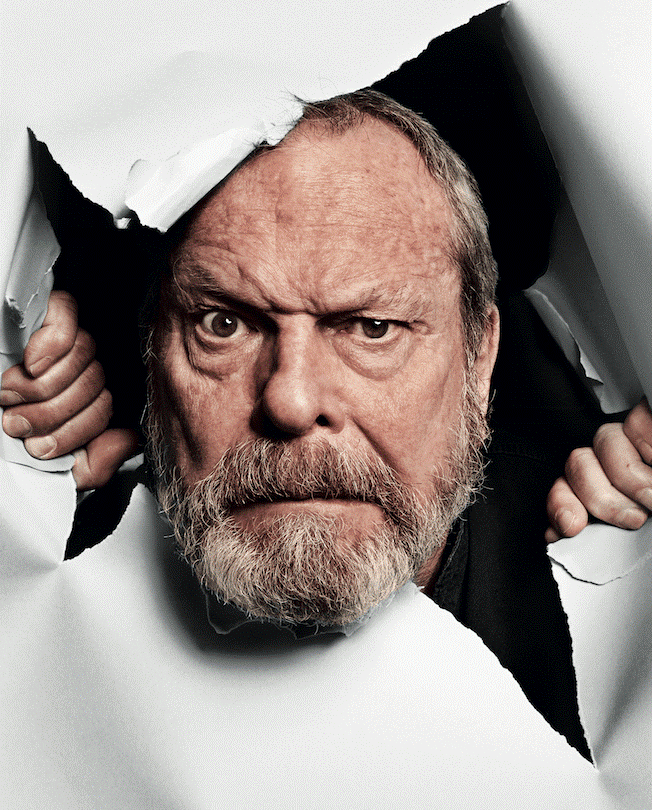

The 29th edition of the Umbria Film Festival in Italy is kicking off today, and its honorary president, Terry Gilliam, has plenty to say about his long and varied career as filmmaker, funny man and provocateur.

The fest, which runs through Sunday, will feature a Saturday event dubbed “Becoming X into the Gilliamverse,” an artistic/musical intervention by the Becoming X cartoonists’ collective, which is dedicated to the 40th anniversary of Gilliam’s legendary dystopian sci-fi comedy Brazil. “To cap off this day, a live drawing will take place in Piazza San Francesco, immediately following the film’s screening,” reads the festival website.

Gilliam talked to The Hollywood Reporter about the film’s anniversary, the state of his planned next film The Carnival at the End of Days and how President Donald Trump may have contributed to its delay.

Happy birthday, Brazil! Can you believe your film is 40 years old? I recently rewatched it, and it feels so timely. How do you explain that?

Clearly, I’m a prophet. Very simple! (Laughs.) I don’t know. The world has always been like this. I just looked at [the future] back then, and I thought about what it was going to be like. I guess most people don’t think about long-term events.

You have had Hollywood hits and some films that weren’t hits. How do you feel about your relationship with Hollywood?

It’s actually been quite fine. I mean, my introduction to it was Time Bandits, which every studio turned down. And then we did it, and it was no. 1 for five weeks. So, I was a golden boy. I was hot. And so, rather than doing a big studio film that I was offered, I said now’s my chance to do a film I want to do, Brazil. And that film then started my relationship with Hollywood, with [then-Universal boss] Sid Sheinberg. So I was off to a rather interesting start.

And then I got my comeuppance and my kind of Orson Welles moment with The Adventures of Baron Munchausen. It went completely chaotic. It was partly because of David Puttnam, who had originally started the film, two weeks after we started shooting got fired [at Columbia Pictures], and then it was left in the hands of the studio. Of course, the new people at the studio wanted to make sure that the previous group of people running the studio looked bad. Dawn Steel got me to cut five minutes out of the movie to get it to two hours long. And she said if I cut it, she’d be behind me, powerfully. And then I did the cut, and they released only 117 prints of the film. That was at a time when every other film got 2,000-3,000. They completely buried Munchausen, I think.

What’s funny is I watched the new 4K version, sitting there thinking: This is a fucking great film. I really genuinely felt that. I felt I was watching a wonderful film that’s funny, but many people never saw.

Since you mentioned funny, you have always had a reputation for humor, sarcasm, caricature and all those things, but you have expressed concern in the past that irony was disappearing. How do you feel about the state of humor, or lack thereof, these days?

I think Trump has changed things considerably. He’s turned the world upside down. I don’t know if people are going to be laughing more, but they’re probably less frightened to laugh. There have been woke activists with a very narrow, self-righteous point of view. That’s frightened so many people, and so many people have been very timid about telling jokes, making fun of things, because if you tell a joke, these people say you’re punching down at somebody. No, you’re finding humor in humanity!

So, irony, satire were basically dead. And humor, to me, is probably one of the most essential things in life. You’ve got six senses, and the seventh sense is humor, and if you don’t have that, life is going to be miserable.

Has the return of Donald Trump also affected your work?

Well, he’s fucked up the latest film I was working on. Because it was a satire about the last several years when things were going as they were. He’s turned it upside down. So he’s killed my movie.

That’s The Carnival at the End of Days, right?

Yes. I had a sub-title that said: “Great fun for all of those who enjoy taking offense.” That was how I approached it. I think Trump has destroyed satire. I mean, how can you be satirical about what’s going on in the way he’s doing the world?

With Carnival, the other day I was thinking I was going to put a little preamble on it saying that what you’re about to see takes place during the period historians refer to as the Trump lost years from 2020 to 2024.

Do you think that there might still be a way to do the movie, maybe in a few years?

I think I’ve got to rewrite a lot of it. I’m still trying to decide how to approach that.

You have a star-studded cast that was going to make this movie with you, right?

Yes, if we ever make it. Jeff Bridges is the voice of God. Johnny Depp is playing Satan. So the cast is rather good. Adam Driver, Jason Momoa, Asa Butterfield, Emma Laird and Tom Waits. You’d think everybody would be rushing forward to give me all the money I need. It’s not as easy as that.

I read once that Quentin Tarantino told people that you gave him some great directing advice. When was that?

That’s why on Reservoir Dogs I’ve got a thank you from Quentin in the film. I was at the Sundance festival, the part where old-timers are supposed to be helping younger directors. And I was there with Volker Schlöndorff and Stanley Donen. All three of us read the script for Reservoir Dogs, and I was blown away by it. I thought, “Fuck, this is wonderful and extraordinary.” Stanley and Volker, It made no sense to them. And the previous group before us had been very negative on Quentin as well. I said I think your work is wonderful. It’s a great script. And I said, here’s how you direct: Be very clear about what you’re trying to do. Then you surround yourself with really good people, and then you listen to them.

There are all sorts of creatives who cite Terry Gilliam as a role model or inspiration. Are there any creatives that Terry Gilliam looks up to?

Most of them are dead. Fellini is like a god to me. Kubrick was a god. Kurosawa, Buñuel and Bergman. I think those are the big ones.

They’re all different sizes and shapes, different kinds of movies, but they were all filmmakers that constantly surprised me and made me think of things in a fresh and different way. And that’s all I’m trying to do as well. I’m not trying to teach anybody anything. Actually, one of the other great inspirations for me was Mary Poppins — not the film, but the person, the lady. Because she always had a spoonful of sugar that helps the medicine go down. So, if I’m doing a dark and disturbing film like Brazil, I make it funny as well.

Let’s talk about the Umbria Film Festival. How did you first get involved in it?

The festival existed before I got involved. And then I bought a house in Umbria in 1990, and the first film of mine that was shown at the festival before I was honorary president was Adventures of Baron Munchausen. I loved the place. I loved the town of Montone, where the festival takes place and which is beautiful. And I liked the people. And eventually I got more and more involved with it, and I’m still involved. It’s in this small beautiful town, and it’s very, very familial. What’s funny is that when the festival occurs, a lot of the foreigners who live around there in the hills and valleys turn up just for the festival. So you see a lot of people meeting each other for one week every year.

As the honorary president, do you have to draw up a vision statement or anything like that?

I just turn up and welcome people on the first day of the festival. Then, I hang around, and sign autographs. It’s great! Everybody else does the real work.

There is this special event at the festival this year that allows people to dive into the “Gilliamverse.” How would you describe what the “Gilliamverse” is like?

I don’t describe anything I do. I allow other people to describe it. I don’t have a fucking clue what it is. I just do what I do.

Before I let you get ready for Umbria, anything else you would like to mention or highlight?

I want to talk about the film that seems to always get lost when they talk about my films. The one that gets lost is Tideland. And Tideland is one of my favorite films of all the films I’ve done. It just seems to disturb a lot of people. They can’t get over the fact that there’s a little girl alone. She’s not quite alone. Her father has just died, but she’s got the body. That’s the important thing. I love Tideland, and I think a lot of people are just shocked by the film. But I think it’s the sweetest thing I’ve ever done. It’s what a child’s imagination is like. And people are frightened when they discover what children are really like.